Meet Transcription Coordinator Stefan Israel

November 10, 2020

• Asheville, N.C., November 10, 2020 •

This fall, with support from Wunderbar Together, the German Heritage in Letters project has benefited from the help of Dr. Stefan Israel as our transcription coordinator. He’s a co-founder of “Unlock Your History” (www.unlockyourhistory.com), a firm which provides transcription and translation services and specializes in historic German documents. As part of his work with us, he has been helping our volunteer transcribers improve their skills and providing quality control for our publishing process. We asked him to share more about how he became interested in German handwriting and what he finds most rewarding about his career. To sign up to become a transcriber, visit our Scripto page!

Interview and translation by Timothy Neckermann (auf Deutsch)

1. What is your background, and how did you become interested in Kurrentschrift?

I was born in Pennsylvania and spent my early years outside of Pittsburgh before moving to Asheville, North Carolina, in elementary school. I got involved in languages early on, starting with French, then Latin. As my family is German-American, I transitioned to German in high school and later majored in German in college, which led me towards Germanic linguistics. In the course of obtaining my PhD, I spent a lot of time abroad, including upper Bavaria, a year in Freiburg, and a couple of years in Kiel and Schleswig—some of my German roots are indeed in Schleswig-Holstein.

When I was in college, my parents—who do not speak German—asked me to translate some old family letters and postcards that were written in Kurrentschrift, but I was unable to read them. As a result, I ended up teaching myself how to read the letters and received some outside help from my grandfather, who grew up learning Kurrentschrift in grade school in the United States.

2. Which style of Kurrentschrift did you learn first?

I first learned Sütterlinschrift, which is also what my grandfather was taught. He gave me his old textbook from school, which was filled with Sütterlinschrift, and I used this as a way to practice and learn on my own. The great part about Kurrentschrift is that once you have learned one style, you can jump to other styles, allowing you to read letters from multiple regions and diverse dialects.

|

|

|

“Among the first pieces I transcribed was a family postcard [from a community near Flensburg]—I could make out most of the letters, and almost make out the words, but they seemed like badly misspelled German. However, it wasn’t German at all! It was properly spelled Danish! I hadn’t realized that that branch of the family spoke Danish more than German! English, German, Danish, they are all similar, but definitely not the same.” |

3. What makes a letter “hard” to transcribe?

For some writers, their writing is not as clear and identifiable as others. The letters “a,” “e,” and “o” are especially difficult to make out sometimes because some people’s writing makes them seem identical. Therefore, it is crucial to understand the context that the letters are written in—especially the time period. I also tend to pick up on a writer’s consistent habits, such as certain grammatical mistakes or using poetry to describe something. Once I have identified a repeated pattern, I am less likely to get stumped by it later on in their writing.

4. What do you enjoy most about helping people learn more about their letters and other documents?

One of the most rewarding aspects of helping people learn about their letters is seeing their faces light up after they are able to actually read their letters which have been locked away for so long. This “unlocking” is what led us to name the website where I do most of my work “Unlock Your History.”

5. What have you found most interesting about working with German Heritage in Letters and helping transcribers improve their skills?

Working with handwriting is the bulk of what I do, which made the project attractive from the start. Being able to teach and coach transcribers was also very appealing to me. I was a professor of Germanic linguistics for a number of years, among other places, at the University of Pittsburgh and the University of Southern Indiana, so I have always loved teaching. I particularly love seeing students’ “aha” moments. I like to give my students little hints along the way until they get to the point where they can identify and understand the letters themselves. Once they have reached this point, they are essentially teaching themselves, which is very rewarding for me as a teacher. I take inspiration from Rimsky-Korsakov, both a famous composer and a great music teacher. He said at the beginning of each course: “First I will talk, and you will listen. Then I will talk less, and you will do more and more. By the end, I will hardly talk at all.” That is the way to teach, as I see it.

I fretted that I would be toiling to get beginners up to speed, but was delighted to see that our transcribers were already good when it came to Kurrentschrift. A side benefit of the German Heritage in Letters project for me is that I get to see all sorts of letters that I normally would not have the opportunity to see.

6. What are your interests outside of handwriting and vocabulary and linguistics?

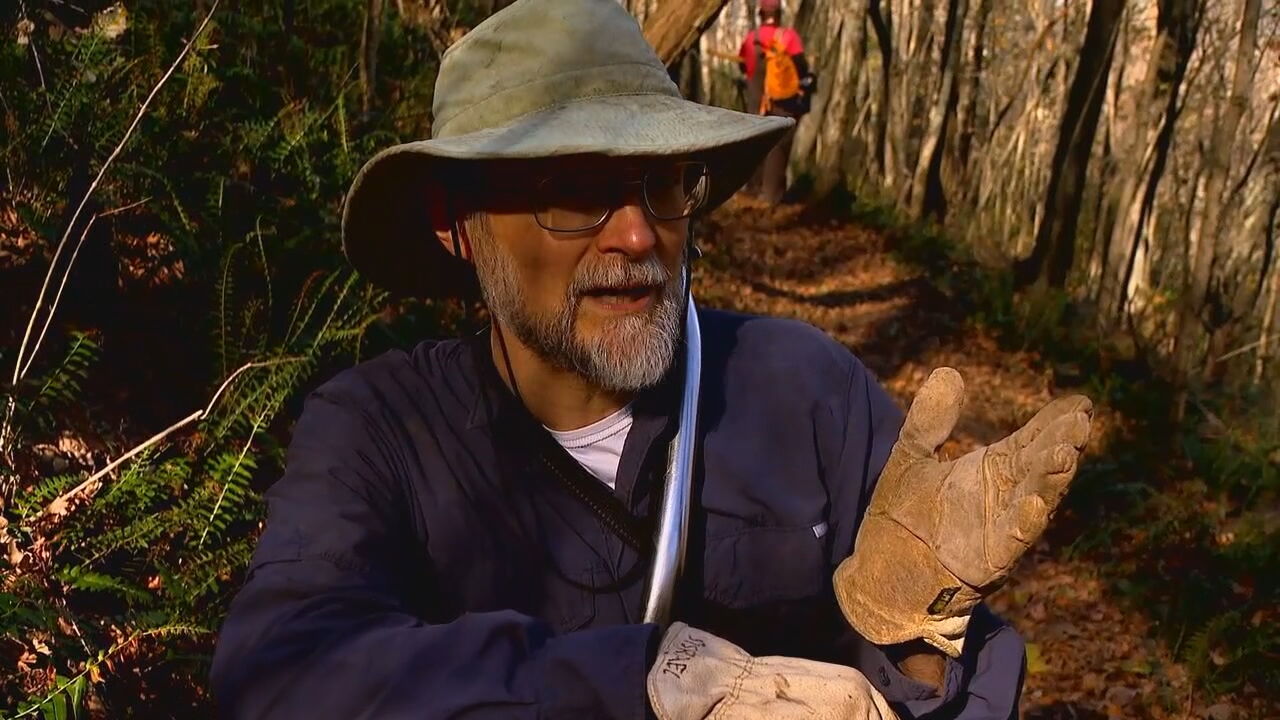

Outside of languages, I do volunteer work creating and maintaining sustainable hiking trails in the Southern Appalachian Mountains, which is where I currently live. The work that I have been a part of will allow the trails to still be around and in good shape 100 years from now.

|

|

Stefan Israel (bottom right) conferring with a group of volunteer German Heritage in Letters transcribers in an online meeting |

Stefan Israel discussing his participation in a group of volunteers who keep North Carolina hiking trails in good condition (photograph courtesy of WLOS-TV) |